When I was studying Physics at University, I deeply fell in love with one “quantity” or “concept”: that of the ENTROPY of a system.

Perhaps you have not heard of it, but it is so important that in some ways it relates to:

- Time itself

- Disorder

- Information

- Energy

- Optimisation

- Economics and much more…

I find it incredibly interesting that the time evolution of the universe in a direction (universe from the Latin means one direction…please do not think of the boy band!) rather than another, is still a fundamentally unknown property of reality. In fact it appears that systems processing information (like us), wouldn’t perceive time if it weren’t for a particular tendency of Entropy to increase (also, we would be immortal too!).

Closing the Physics parenthesis, in the context of this blog post, I can tell you that I will see Entropy as a measure of “disorder”, and also as a measure of “information” contained in “something”.

To be more explicit, I see something possessing a high level of disorder if, by changing it slightly, it doesn’t change the way I see it. For example, if your desk is a mess (high disorder), I can move some paper from the left to the right, and I still basically see a messy desk. If your desk is tidy (low disorder) and I put a t-shirt on it… I easily perceive that something isn’t as it should.

Also, when I refer to the information possessed by something I mean pretty much the number of “meaningful” answers to straight yes/no questions that something can give me. Here “meaningful” is not defined but I hope you can follow.

What does this have to do with fraud analytics?

Let me put it this way asking you a couple of questions:

- Do you think that when a certain system (you could think of a payment processor infrastructure, or a trading desk) is being cheated, will the system be more or less tidy?

- Do you think that the information of a system where fraud happens is larger or smaller than a normal system?

When fraudster do act, they do not act randomly, they act on purpose and follow patterns, therefore your system could show signs of being “more tidy” than usual. For example, processing several hundreds payments of the same amount, or seeing traders all following a particular investment strategy (perhaps suggesting insider trading?) might not be a natural state of affairs.

When you see something following a pattern, you instinctively think that there is SOMEONE behind it… in other words it cannot be random. This is equivalent to say that Entropy tend to be high, unless we work to make it low (e.g. sorting out your desk).

This is when Entropy can come in and help fraud analysts monitor the system and see if too many patterns are emerging.

It can get even more interesting since we can also calculate the Entropy of X given Y. Therefore we can also analyze relationships with all the weaponry that statisticians can use to establish relationships.

Let’s look at some numbers.

Here’s a vector of random numbers: 52 31 22 52 100 46 11 24 77 21

Here’s a vector of not so random numbers: 10 10 10 20 20 20 30 30 30 100

Using R (the statistical computing language), for example, we can calculate the Entropy of the random collection of numbers. We get 2.16 (don’t care about the units for now).

If we calculate the Entropy of the not so random vector we get 1.3.

But let’s now add some additional information and context. Let’s consider the vector of not so random numbers as the amount that was withdrawn on certain days. Let’s also look at the days: Mon, Tue, Wed, Tue, Wed, Thu, Thu, Fri, Sat, Sun.

Now what’s the Entropy of those cash withdrawals given the days they were made?

o,4

That tells us that this is a pattern, not necessarily a fraudulent one, but if we have a hypothesis over the average Entropy of cash withdrawals we could somewhat understand if a Bot/Fraudster has brought order where there shouldn’t be!

Overall, thinking of utilising Entropy in any analytics related matter is a fascinating example of the variety of tools, and sources of inspiration, that can help data professionals (and data driven organisations) in achieving their objectives.

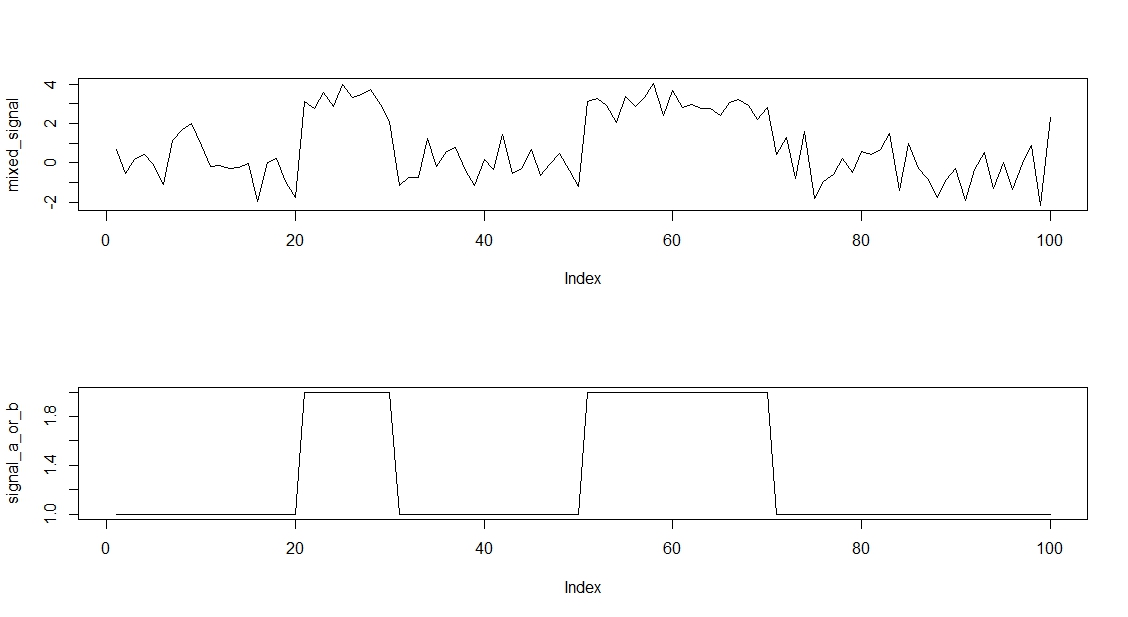

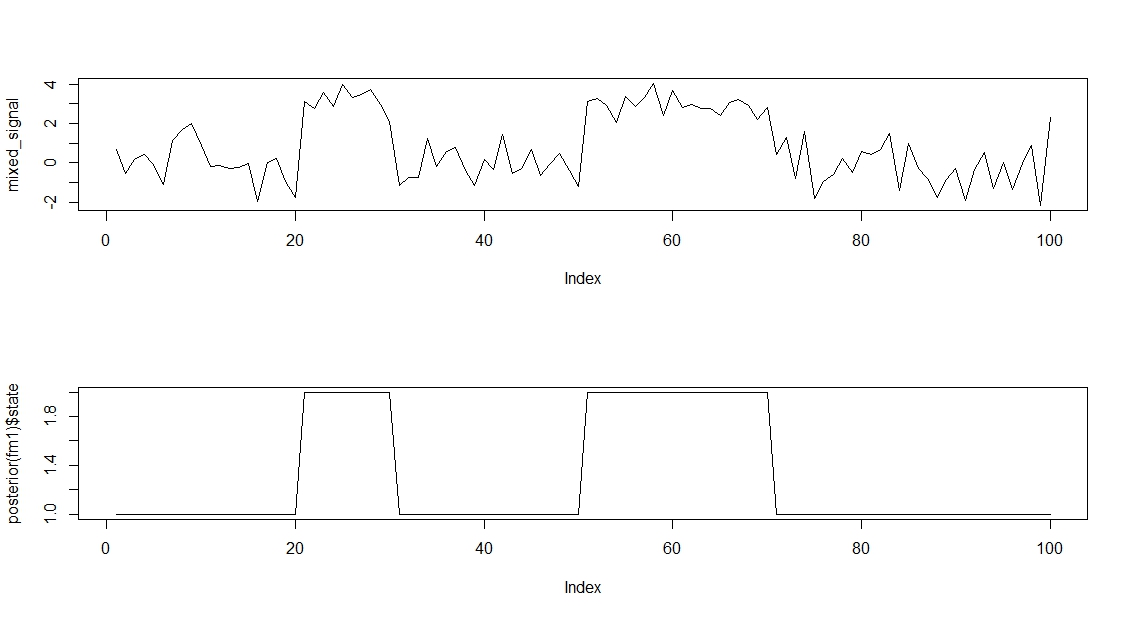

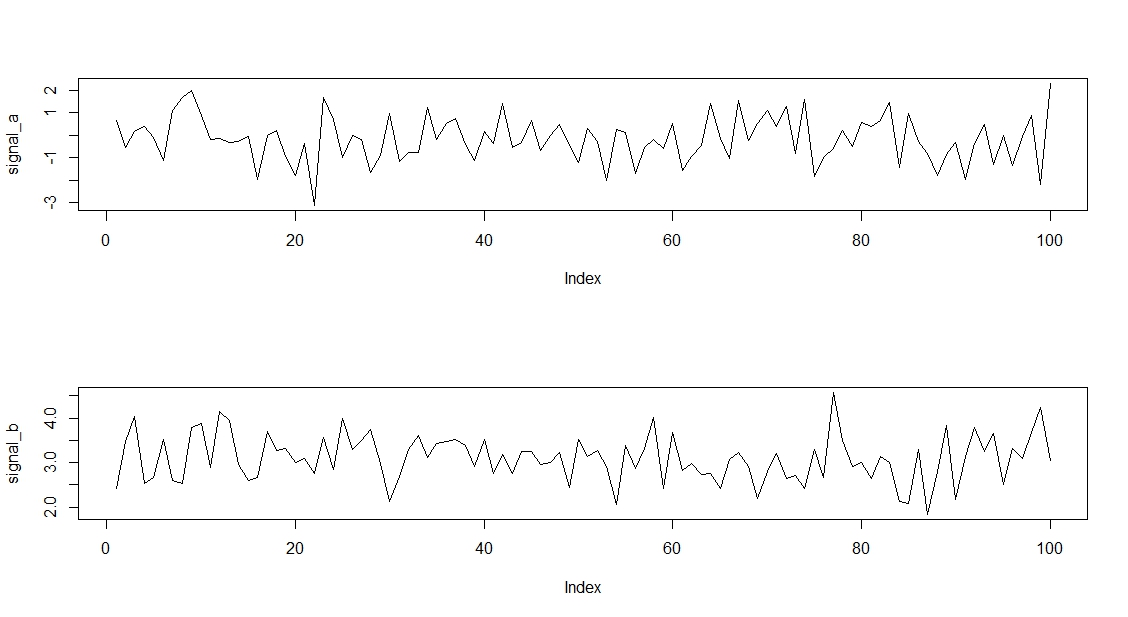

As you can see the two signals are not so different, so it won’t be an easy feat.

As you can see the two signals are not so different, so it won’t be an easy feat.