As I write this blog I am surrounded by a social/political dialogue that does not seem to proceed, or be guided, by the standards and signposts I was educated to follow to aim for progress. It is all quite confusing and this has brought back memories of a great hero of mine: Galileo Galilei.

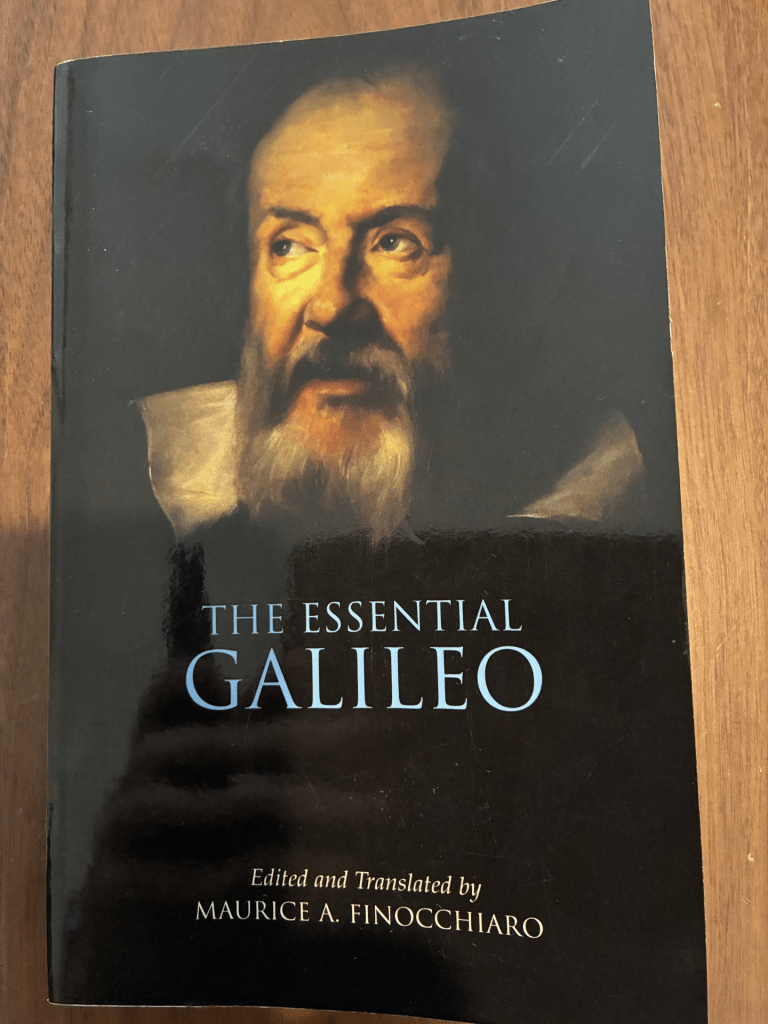

The man in the image below:

Galileo lived ~500 years ago and he is largely credited as one of the driving forces of the scientific revolution. That is the revolution that took us from 1-2bps of growth in output and standards of living for hundreds of thousands of years, to the skyrocketing acceleration of innovation, and quality of life, of the last few hundreds years. We all hope this pace will continue for as long as possible.

When I grew up I did get the point that Galileo was a genius, and that he was prosecuted for his heretic ideas about the Earth moving around the Sun, but I did not understand, as much as I do now, how fundamental his life and example had been in driving change and progress in a world that was intellectually paralyzed for millennia.

When Galileo started his scientific career, to be educated meant to be able to understand the body of Aristotle philosophy, the Bible, and to have a good account of Geometry as it was developed by the Ancient Greeks.

Instead of focusing on “How do we know, explain, or understand such and such…” the prevailing framework was to argue on the basis of “by what authority do we claim?”. The latter and prevailing intellectual tradition led to what is called “Scholasticism”. Scholasticism basically meant that everyone’s effort was to come up with some sort of top down explanation about facts that had to be aligned or, even better, justified by some passage of what Aristotle wrote, or what was in the Bible.

Facts and reason did not matter as much, it was all about narratives and how good a story was and how well it aligned with “first principles”, or whatever fashion was prevailing in a given epoch.

For example Aristotle, who was nevertheless a great philosopher, envisioned a world where Earth was at the centre, and somehow at the bottom of the universe, which, in his view, explained why everything fell down. He also devised a world in which different substances behaved differently, but everything liked to move in circles, the argument was that circles are perfect.

Aristotle never tried to really test his theories as we would do today, after Galileo’s lesson. All he did was providing plausible arguments and sensory examples. In this sense he was an empiricist, but not a scientist. I will clarify the distinction later, but here’s an example.

Aristotle observed that large bodies seemed to fall harder to the ground, and that very light and thin ones didn’t. He then provided an explanation that sounds “common sense” in his philosophy. Heavier objects have more “matter” and long to reach Earth, the mother of matter, as quickly as possible, others are happy to take a bit more time as they are also part of a substance that longs for the heavens (like air).

Believe it or not this was then to be the prevailing understanding of how things move for about two thousand year, in Europe at least – crazy how well a story can sell right?

Nevertheless Aristotle was wrong on all accounts (when it comes to Physics).

Here’s how this has to do with Galileo, and science. Galileo was of a different temper since he was young. He thought that all the philosophical speculations were a lot of fun, but that ideas needed to be accountable before reality. Galileo didn’t just believe in “experiments” and gathering data, what we called empiricism, but he developed an approach that was tougher and gave birth to western science in the process. Galileo thought ideas and conjectures needed to be put on “trial”. In italian he called that “cimenti” which, for the fans of Game of Thrones, best translates to “trial by combat”.

So when Galileo decided to investigate the motion of objects, he immediatly sought to test his view that objects moved following specific geometrical and mathematical laws, with the view of Aristotle, and famously dropped objects from the leaning tower of Pisa and behold!:

After two millennia someone actually bothered to find out that, after all, objects of a similar fabric, but of very different weights, fall at the same speed! (his “cimenti” actually were on inclined planes but… the power of a story). And in a fierce trial by combat Aristotle theory lies on the ground, dead as a stone. This is the key difference, Galileo didn’t tell stories about how his view “made sense”, he took is idea and put it out there, fly or get killed.

Why did it take two thousand years? – That is a long story, but we can all testify that the behavior that was followed for millenia is still around us: believe in authority, don’t ask quetions, optics are all that matters, tell a good story, its common sense etc.etc..

Galileo was, as Aristotle, also a great debater and writer and in his famous books written as dialogues he indeed asks the question to Simplicio, he goes:

“But, tell me Simplicio, have you ever made the experiment to see whether in fact a lead ball and a wooden one let fall from the same height reach the ground at the same time?”

This is science: truth is not determined by who said what, common sense, or examples, but by what nature/reality reveals when cornered. We discover the truth, we do not and should not create it!

This spirit is what led to the cures that help us when we are sick, and the tehcnologies that improved our lives beyond the wildest imagination of anyone living in Galileo’s time. This is what made progress scalable: a method to drive progress, that can be distributed everywhere. Everyone can pick things up from where Galileo left them today, and do the experiment and move things forward, there is no authority, no story or view to follow, no boundary beyond honesty.

This matters everywhere. In politics, in science, and indeed in business.

But Galileo was also a revolutionary genius specifically within Physics and I do want to close with what we today call the “principle of relativity”, and how Galileo deeply unlocked the power of imagination in science. This seems a contradiction as you might now think that Galileo was weary of speculations, but the truth is the opposite, once he provided an effective method for progress, he then unleashed imagination in a productive way.

Most pople that did not to go far in enjoying the study of science, and physics, believe that what is hard about science is something like the math, the jargon, or the baggage of things to memorize. In truth the concepts are hard, the formalism is often very easy and mechanical.

Listen to what Galileo said about motion carefully. Galileo observed the following:

“No one can actually tell whether he or she is moving, velocity is not real, there isn’t physical fact about velocity, as velocity is only but relative” (this was an important point for him to support that Earth was moving around the Sun).

He then goes on to the famous example of one sitting below deck in the cabin of a smooth sailing ship, where you won’t be able to tell whether the ship is moving, or not, in any way.

He was right but this concept is tough, how can velocity be an illusion? If the change in velocity (acceleration) is real, and we can tell if a ship is changing its speed, how can velocity not be physically real? How can the change in something “unreal”, like velocity, be real, like acceleration?

I won’t answer those questions now, but I hope the thirst for knowledge will push some of you toward picking up a physics and classical mechanics book to find out more, but my point is the following:

You don’t need maths and all the techincal baggage to understand more about Galileo and his science.

And my broader point is what is most at my heart in writing this blogpost:

You don’t need any title to go out there and defend what has served us well, and lifted us after hundreds of millenia of no progress, which is the methodical pursuit of truth, useful truth, I would say. Facts matter, reality is out there. Opinions, narratives, stories, optics, bad formulas and all that alone do not move us forward, they never did and never will.

We should all embrace the “cimenti” , the trial by combat of our scientific tradition, first and foremost on our own ideas and conjectures and never forget we are aiming for progress not fabrications.

To get a quick view on Galileo’s life and key ideas I recommend the following book: