I have studied statistics and probability for over 20 years and I have been constantly engaged in all things data, AI and analytics throughout my career. In my experience, and I am sure in the experience of most of you with a similar background, there are core “simple” questions in a business setting that are still very hard to answer in most context where uncertainty plays a big role:

Looking at the data, can you tell me what caused this to happen? (lower sales, higher returns etc.etc.)

Or

If we do X can we expect Y?

…and other variation on similar questions

The two books I have read recently focus on such questions and on the story of how statisticians and computer scientists have led a revolution that, in the past 30-50 years, succeeded in providing us with tools that allow us to answer those questions precisely (I add “precisely” since, obviously, those questions are always answered, but through unnecessary pain, and often with the wrong answers indeed).

Those tools and that story is still largely unknown outside of Academia and the AI world.

Let’s come to the books:

1 – Causal Inference by Paul R.Rosenbaum

2 – The Book of Why by Judea Pearl and Dana Mackenzie

Both books are an incredibly good read.

Causal Inference takes the statistical inference approach and it tells the story of how causes are derived from statistical experiments. Most of you will know the mantra: “Correlation does not imply Causation”, yet this book outlines in fairly simple terms how correlations can be leveraged and are indeed leveraged to infer on causation.

Typical example here is how the “does smoke cause cancer?” question was answered, and it was answered, obviously without randomised trials.

The Book of Why is a harder read and goes deeper into philosophical questions. This is natural given the authors are trying to share with us how the language of causation has been developed mathematically in the last 30 years, and the core objective here is to develop the tools that would allow machines to answer causal queries.

I want to get more into the details of some of the key concepts covered in the books and also to give you a sense of how useful the readings could be.

Starting with Rosenbaum’s I would point out that this books is even overall a great book to get a sense of how statistical inference, and the theory of decisions under uncertainty, is developing.

This book is a gem, no less.

It starts very simple with the true story of Washington and how he died after having been bled by his doctor (common practice back then) and asks: Would have Washington died, or recovered, had he not been bled?

He then moves to explain randomised trials, causal effects, matching, instruments, propensity scores and more.

Key here is that the only tool for statistical inference that was well developed and accepted up to the 70s was the randomised trial, that is, for example in medicine, giving a treatment to a random sample of individuals, a placebo to the others and check the difference in outcomes to make inferences.

This procedure itself is not even causal, in principle it is still flawed with respect to answering a causal query (logically), but it works as follows:

- I see outcome O associated with treatment T

- What are the chances that I would see O regardless of treatment T?

- If chances are low, that is evidence of treatment T causing outcome O (unlikely association after all is interpreted to imply causation)

Rosenbaum goes to explain why above works in the causal inference framework, as it is interpreted as a counterfactual statement supported by a particular type of experiment, but then moves to explain that even observational studies (where there is no placebo, for example) can provide answers that are as robust as randomised trials/experiments.

Other key points are really on the struggle that the statistical community had to go through and goes through today when working through observational studies. It is of note the historical account of the debate when the relationship between smoking and lung cancer was investigated with the unending “What ifs”… what if smokers are less careful? what if smokers are also drinking alcohol and alcohol causes cancer? etc.etc.

An illuminating read, which also sheds light to how the debate on climate changes is addressed by the scientific community.

Moving on to The Book of Why

I love one of the statements that is found earlier in the book:

“You cannot answer a question that you cannot ask, you cannot ask a question you have no words for”

You can tell this book goes deeper into philosophy and artificial intelligence as it really aims to share with us the development of a language that can deal with posing and answering causal queries:

“Is the rooster crowing causing the sun to rise?”.

Roosters always sing before sunrise, so the association is there, but can we express easily in precise terms the obvious concept that roosters are not causing the sun to rise? Can we even express that question in a way a computer could answer?

The authors go into the development of those tools and the story of what hindered this development, which is the “reductionist” school in statistics. Taking quotes from Karl Pearson and his follower Niles:

- “To contrast causation and correlation is unwarranted as causation is simply perfect correlation”

- “The ultimate scientific statement of description can always be thrown back upon…a contingency table”

The reductionist school was very attractive as it made the whole endeavour much simpler, and mathematically precise with the tools available at the time. There was a sense of “purity” to that approach, as it was self consistent although limited, but indeed attempted to imply that causation, which was a hard problem, was unnecessary (best way to solve a hard problem right?). Ironically, as the authors also point out, this approach of assuming that data is all there is and that association are enough to draw an effective picture of the world, it is something that novices in machine learning still believe today (will probably talk more about this in a later blogpost).

Pearson himself ended up having to clarify that some correlations are not all there is, and often misleading. He later compiled what his school called “spurious correlations” which are different from correlations that arise “organically” although what that meant (which is causal correlations) was never addressed..

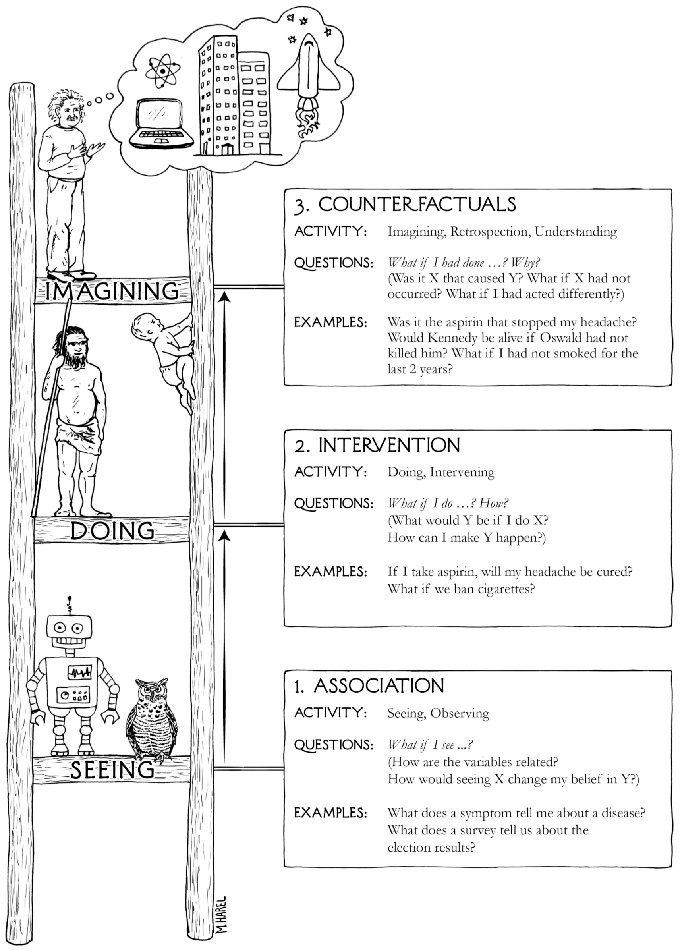

The authors also introduce the ladder of causation, see below:

Which is referenced throughout the book and it is indeed a meaty concept to grasp as one goes through the 400 pages of intellectual mastery.

What Pearl and Mackenzie achieve, that Rosenbaum does not even aim to discuss, is to invite the reader to reflect upon what understanding is, and how fundamental to our intelligence causality is.

They also then share the tools that allow for answering very practical questions, e.g.:

Our sales went up 30% this month, great, how much of it is due to the recent marketing campaign and how much is it driven by other factors?

The data scientists among you know that tools to address that question are out there, namely structural equation modelling and do calculus, but this indeed is closely related to structural causal models that Pearl promotes, and, in ultimate instance, the framework of introducing causal hypothesis is unavoidable.

Conclusions:

I recommend the books to any knowledge seeker, and anyone that is involved decision making (or selling benefits that are hard to measure).

I would start with Rosenbaum’s book as it is less than 200 pages and, if time is scarce I would prioritise reading Pearl and Mackenzie’s book up to chapter 6 first (190 pages)