Due to the nature of my profession I am often engaged in conversations that revolve around the definition, the role and the potential of data science and artificial intelligence. Often the conversation start out of the desire to understand how to use this new bag of tools called “data science”… typical case of a solution trying to find a problem. I am not criticising this approach per se, it’s only natural that a relatively new discipline will go through this exploratory phase, but I am observing that the conversation often starts away from data scientists and data professionals in general.

At the core of those conversations is the desire to outline a data science strategy in a business context.

The issue is that the knowledge necessary to have a fruitful discussion is, sometimes, technical in nature and, therefore, I will now share an important technical aspect of doing data science that I believe even scales up to be a guiding principle for more general business strategies: the bias-variance trade off.

It is a fact of statistical learning that the error of predicting models is the sum of an error due to bias, and an error due to variance (note: variance of the model not the data).

In other words our predictive models will either be too stable and be wrong because of strong assumptions (BIAS) or too unstable due to sensitivity to data points (VARIANCE).

You could also use the terms under-fitting and over-fitting, but fitting sounds technical as well.

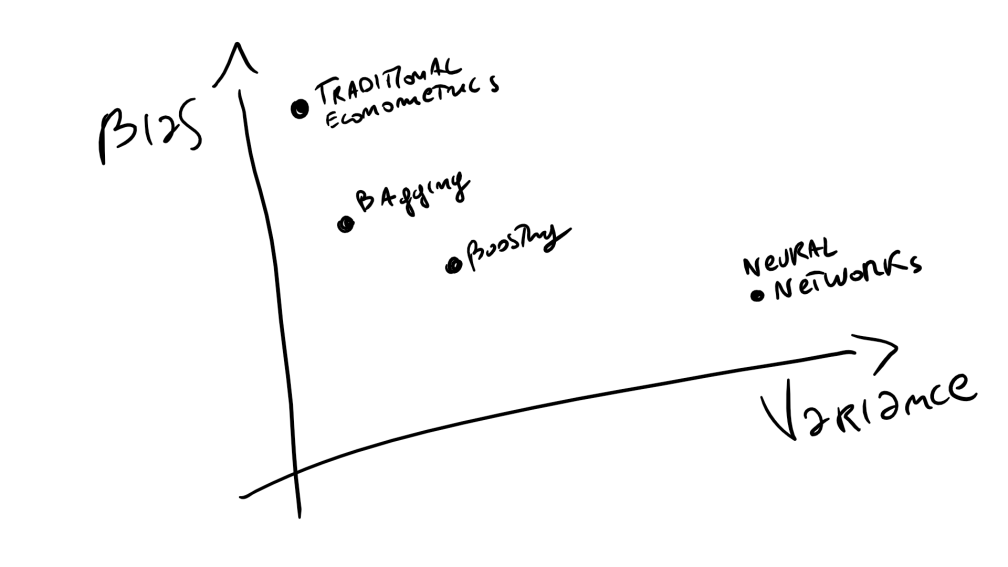

The drawing below shows where some popular data science techniques stand in this two dimensional scale (bias & variance):

Old traditional methods often have strong assumptions (like simple linear models), yet provide decent and, most importantly, coherent results when the data is updated. Whilst some of the most modern methods try to dispense as much as possible of assumptions and rely completely on data, yet can produce nonsensical results if the data varies too much, or if the data does correctly represent nonsensical behaviour.

It is also then consequential that low-bias methods need much more data (unless the data is highly structured), and can’t be used lightly in contexts where it is the objective to model general behaviours (like forecasting).

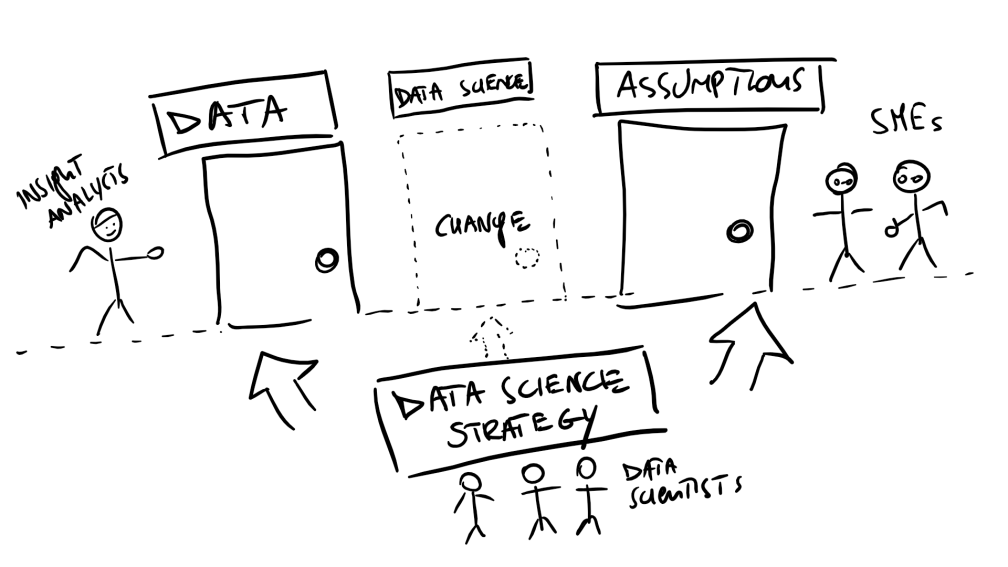

Historically we see then that businesses have relied on the two types of approaches being performed by different units. Subject matter experts providing forecasts (for example) and insight analysts providing complex numerical tables and charts. The first category being (generally) formed by biased experts (e.g. the product will sell 10% more if priced down by a fifth) and the second by research types looking impartially at the data (the chart says that your customers are already unhappy with the price yet buying your product). Inevitably, in several occasions, it turns out that the SMEs are right if the price is changed exactly by a fifth but terribly wrong otherwise, and the researchers have drawn conclusions from a small sample of customers with unclear methodological issues.

The drawing below sort of summarises the above paragraph:

Now, when I think “what can data science do for this organisation?”, my technical brain somewhat answers: it can help the organisation strike a better bias-variance trade off! and this actually means business transformation. Data science can bring together the insight and product teams, data science can also bring management close to customers and partners, and all this by simply striking a better balance between a business instinct toward common practices/assumptions (bias) and a business need to react quickly to new information (variance).

We can easily see that the two dimensions are not bad at modelling decision making in several other aspects of life, e.g. will I vote the party I always voted for (bias/assumptions) or stick strictly to the manifesto commitments (variance/data).

It is also a good framework for prioritising items in a data science transformation (net of business value), e.g. if you don’t have customer data, start collecting it and keep relying on smart and experienced marketers, whilst if your products data is in a good place start developing advanced models on cost effective production and quality control.

Data science is pretty much a discipline born out of the growth of available data and, therefore the possibility to move away from bias. Ignoring this fact when designing a data science strategy is akin to ignoring what a long catapult could do in the middle ages.

You can lose the war for it.