Perhaps you might know that I am rather interested in “latent variables” that is: hidden signals.

Why is that?

Let me put it simply. 99% of statistics is about doing one thing very well: distinguishing signals from noises.

You want to know if that stock price is fluctuating in a worrying way?

You need to check whether those fluctuations are statistically common (noise) or if we see something “unlikely” or unprecedented (signal).

Also, generally, you’d like to test how confident you are in distinguishing signal from noise (but a lot of people don’t actually do this).

The beauty of latent variables, and, in particular, of Hidden Markov Models (HMM) is that you are actually trying to discover a “secret” signal.

The secret signal could be a fundamental signal underlying a phenomena, or even data that actually explains the relationship between two different processes.

This is something that opens a world of possibilities.

Let me give you an example, a very simple one.

An individual uses his/her credit card every now and then, but more so towards the end of the month and, generally, for restaurants and entertainment.

Now, this individual finds a second half, and he/she starts using the same card since the card comes with discounts and points.

The signal changes completely, and, if the credit card issuer does any analytics, it might believe that the particular customers is spending more (great!) and they have gained share of wallet (great again).

On the other hand there is only one account owner and now all those card linked offers are all over the place!

Here there is a missed opportunity: the credit card company should actually propose a complementary card to acquire a new customer and then send appropriate offers.

But, how to know that? Hidden Markov Models.

An HMM algorithm could tell us pretty simply that there is another signal underlying the purchases: she is buying or he is buying, a simple binary signal.

Let’s look at an example.

In R the package depmixS4 is the package to use to fit HMMs.

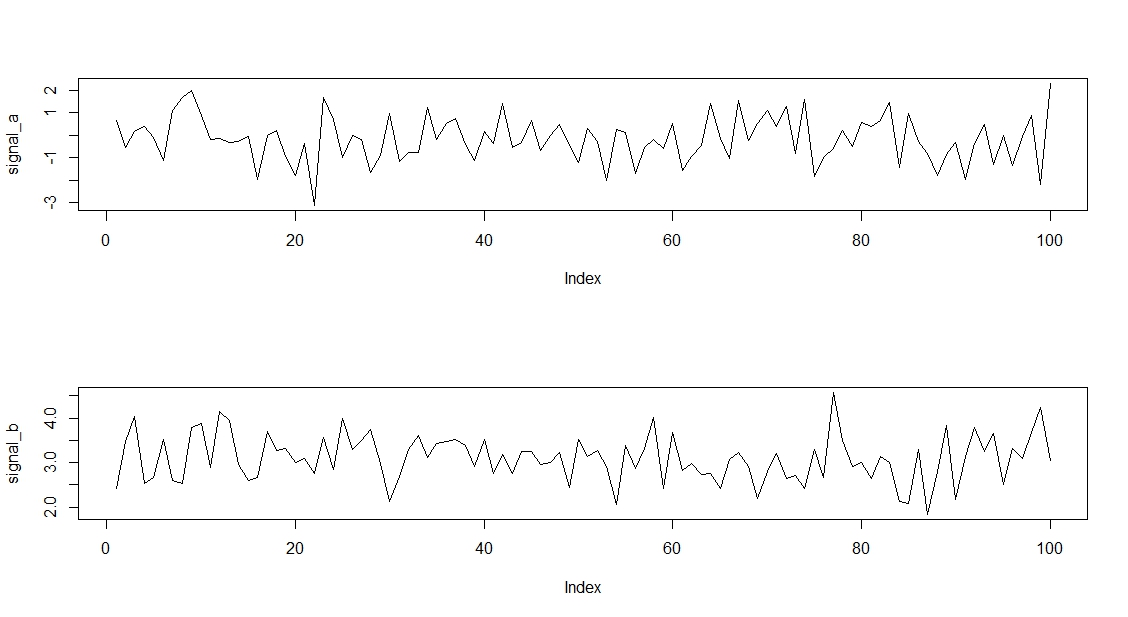

We create in R a signal that is actually made of two distinct signals

library(depmixS4) library(markovchain) signal_a <- rnorm(100,0,1) signal_b <- rnorm(100,3,0.5) plot(signal_a, type ="l") plot(signal_b, type = "l")

As you can see the two signals are not so different, so it won’t be an easy feat.

As you can see the two signals are not so different, so it won’t be an easy feat.

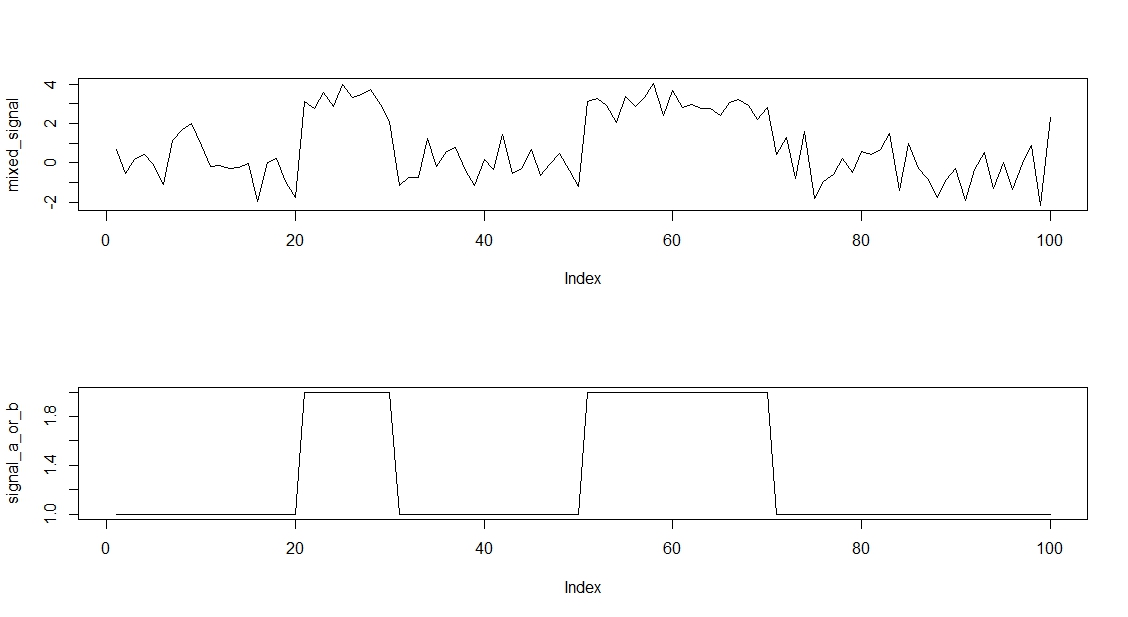

Let’s look at the mixed signal:

I also put the underlying and true mix of the two signals.

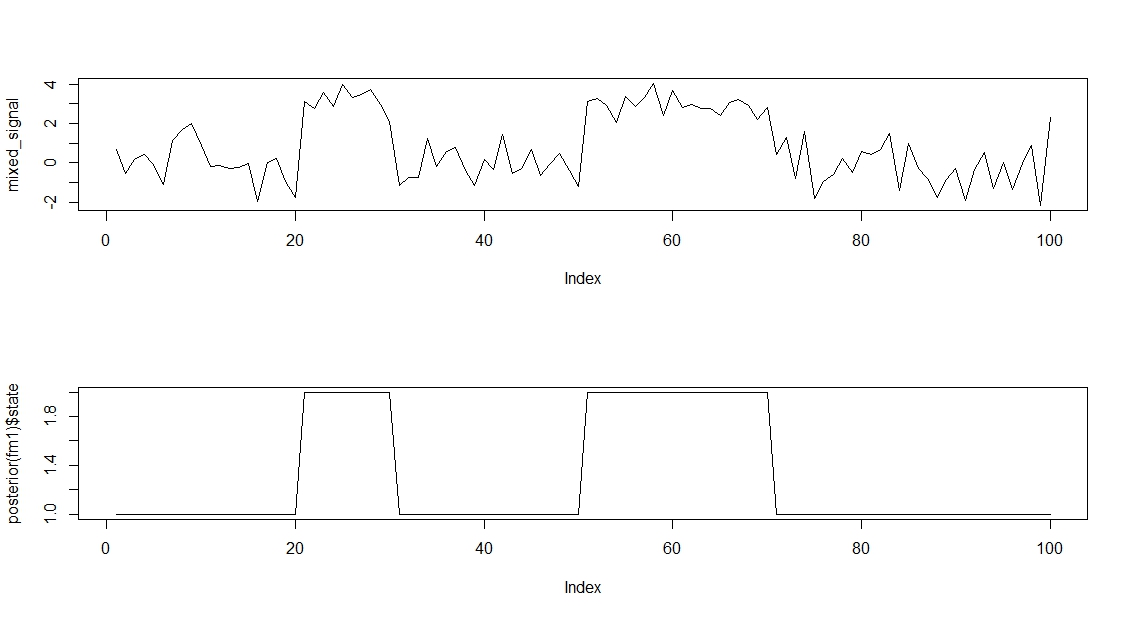

Now, let’s see how an HMM algorithm can understand that we have mixed two signals:

y <- data.frame(mixed_signal) m1 <- depmix(mixed_signal~1, data = y,ntimes = 100, nstates = 2, family = gaussian()) fm1 <- fit(m1) summary(fm1) par(mfrow =c(2,1)) plot(mixed_signal, type ="l") plot(posterior(fm1)$state, type = "l")

As you can see that is a pretty solid discovery of a hidden signal!.

Why does this matter?

Philosophically I would say that being one step closer to the truth is satisfactory in itself, but commercially, knowing underlying signals can mean Money.

How?

This will be for a future discussion, but, let me tell you this, organisations have to start pricing their information or lack of thereof.

We cannot have analytics professionals that are not able to put a money value on a model.

In the credit card example it would, perhaps, be easy.

Just answer the following questions:

- What is the additional spend that we could forecast having two customers with distinct cards?

- What is the additional revenue of being able to have two clear signals for the card linked marketing department?

This is fun and it is money.