There is one coefficient in statistic that is used and misused by more than any other:

THE CORRELATION COEFFICIENT

Generally speaking you might be doing some market research and you come across two variables and you want to see how they are related. How to do that in its simplest form?.

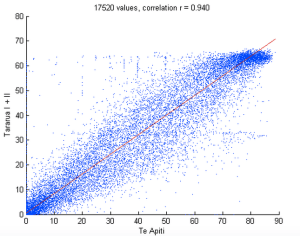

Easy let’s use the correlation coefficient. Then, usually, practice goes that if the correlation coefficient is greater than 0.6 we believe there is a relationship worth further investigation, and/or actions.

There are things to bear in mind when talking correlations though, and in particular that:

The coefficient of correlation only detects linear dependence.

It is important to consider the variables that we have at hand and judge if we generally think that if a relationship exists, that has to be linear.

In several cases this won’t work but with a bit of thinking before just using a line of code things can make more sense.

For example let’s suppose we are pondering an investment into a retail outlet and we want to see if there’s enough population, and not enough competition, in the area to sustain the business. Let’s imagine it is not a simple coffee shop but a rather less common service like, for example, a guitar shop. Now it is the case that we did some research in a similar area and check how many individuals go to a certain guitar shop depending on the distance. After calculating the correlation we don’t see a strong relationship therefore one of the investors seems to push for it on the assumption that it will be possible to attract customers from far away given the nature of the business… distance won’t matter too much.

Or so it seems, but after applying a simple transformation, for example taking the inverse power of the distance we see that the correlation is much higher… How to interpret this?

Well, the solution is simple. The simple distance is linear but the drop in individuals going to the shop is much higher moving from 2 to 4 miles as compared to the drop moving from 1 to 2 miles. This is usually a fact of life and not just for gravity.

In this case it would be easy to spot the transformation that makes it clear to us that the correlation is strong, but what if we are in the presence of more exotic parameters?

One of the options is to normalize the variables to correlate through the Box-Cox transformations. In this way we have the variables being both normal and to some extent linearized. I strongly recommend variables are linearized before trying out correlations that have a strategic weight.

Luckily for us R has a package with the right instruction:

The library is car, and the function to use is powerTransform.

Now I advice you don’t go checking all the correlations that influenced your research decisions in the past using this transformation, you might just find out you were wrong.